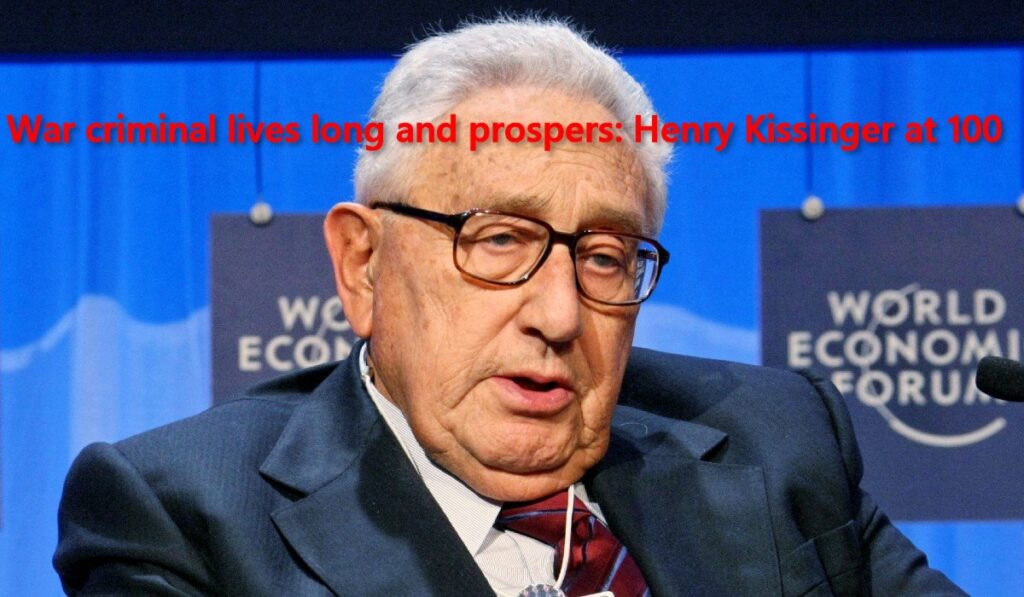

At age 100, Henry Alfred Kissinger is definitely the biggest criminal ever to work for any government

BLOOD ON HIS HANDS – AMERICAS BIGGEST WAR CRIMINAL – HENRY KISSINGER

German born, American government criminal and regime change specialist Henry Kissinger now celebrates his age at 100, after he personally was responsible for killing millions of people world wide.

As the imperialist elite celebrates his birthday, John Clarke outlines the sheer scale of Kissinger’s crimes from Vietnam to Chile, committed in order to preserve the system

One of the world’s most notorious war criminals, Henry Kissinger, is about to reach one hundred years of age on 27 May. In the US, in 2021, there were only 89,739 centenarians, so, in a country with a population over 330 million, it’s fair to say that Kissinger has had a very good innings.

Not only has Kissinger lived long, but he has also prospered, with a net worth of some $50 million, largely attributable to his leading role in Kissinger Associates, an international consulting firm. We may also fully expect that the US establishment and its media will greet Kissinger’s birthday with effusive praise and lavish tributes. He will be honoured as a veritable national and international hero.

In 2015, the US anti-war organisation CodePink ‘attempted to perform a citizen’s arrest on former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger when he testified on global security challenges at a Senate Armed Services Committee meeting.’ It should be noted that the fact that Kissinger was making such a presentation before an official body only eight years ago, is an indication of his enduring status and influence in Washington.

The participants in the CodePink action wished to drive home the criminality of Kissinger on the world stage. They asserted that they were acting, ‘In the name of the people of Chile, in the name of the people of Vietnam, in the name of the people of East Timor, in the name of the people of Cambodia, in the name of the people of Laos.’

The protesters were removed by the Capitol police and the members of the committee were appalled that their illustrious guest had been challenged in this fashion. Senator John McCain asserted that: ‘I have never seen anything as disgraceful and outrageous and despicable’ and, unable to contain himself, yelled at the CodePink activists: ‘Get out of here, you low-life scum.’

Brutal initiatives

In any just society, Kissinger would undoubtedly be held accountable for his appalling track record of war crimes and human-rights abuses. However, his brutal initiatives were undertaken in the service of an imperialist power that had need of his talents. Prior to going into ‘public service’ in 1968, ‘Kissinger was a professor of international relations at Harvard.’ In this academic setting, he had already developed a view that ‘the United States should carefully pursue its own interests’ in such a way that, ‘Moral and ideological considerations … were less important than cold, hard evaluations of what could advance America’s strategic position.’

Once he had become Richard Nixon’s security adviser, and subsequently as secretary of state, Kissinger was able to put the cold cruelty of these political calculations into effect. His pragmatic viewpoint led him to take forward a policy of ‘detente’ that sought some level of normalised relations with the Soviet Union and China. It also meant, however, that poor and oppressed countries would be subject to the most pitiless measures to keep them within the sphere of US domination.

It is hardly necessary to set out in great detail the evidence of Kissinger’s criminality, since this work has already been carried out. Indeed, ‘… the evidence that he aided and abetted war crimes during his time in the White House advising Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford is well-established and overwhelming.’ It is enough for present purposes to take note of some of the key examples of Kissinger’s blood soaked career. In a criminal court, the guilt of the accused rests both on evidence of unlawful action and on establishing criminal intent. In this regard, there is an open and shut case against Kissinger.

Beginning in 1969, the carpet bombing of Cambodia was nominally undertaken ‘to destroy North Vietnamese and Viet Cong bases. In reality, it was designed to improve America’s strategic position before a negotiated withdrawal.’ This carnage claimed the lives of between 150,000 and 500,000 people and generated the destabilised conditions that made possible the horrors of the Pol Pot regime.

In the first stage of the bombing, ‘Kissinger personally approved all 3,875 bombing raids.’ As the late Christopher Hitchens put it, ‘The degree of micro-management revealed in Kissinger’s memoirs forbids the idea that anything of importance took place without his knowledge or permission.’

In 1971, Kissinger viewed the authoritarian regime in Pakistan as ‘an anti-communist bulwark in the region.’ As the struggle to achieve an independent Bangladesh developed, he allowed the murderous repression that Pakistan unleashed to continue, so as to preserve an alliance with its government. ‘He pulled the US consul general in Dhaka, Archer Blood, from his post for questioning the policy, and blocked efforts to pressure Pakistan … to end its slaughter.’

Princeton professor Gary Bass has written that ‘Kissinger joked about the massacre of Bengali Hindus, and, his voice dripping with contempt, sneered at Americans who “bleed” for “the dying Bengalis”.’ The intervention of India finally ended the slaughter but by then it had resulted in a death toll of between 300,000 and three million.

It has also been established that Kissinger gave the ‘green light’ to the 1970s Argentinian Dirty War. This was a round of brutal state repression against working-class organisations and leftists that claimed the lives of some 30,000 people. The Argentinian foreign minister was worried that the US might raise some human-rights concerns over the crackdown but a breakfast meeting with Kissinger calmed his fears. Kissinger only asked him how long it would take to ‘clean up the problem’ and gave the murderous campaign his blessing.

Chile coup

The US role in overthrowing the leftist Allende government in Chile in 1973, through a brutal military coup, offers evidence of Kissinger’s criminality at its most wilful and systematic. He was very clear that it was perfectly permissible to bring down a duly elected government and establish a murderous dictatorship, in order to further US interests. As he put it, ‘I don’t see why we should have to stand by and let a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.’

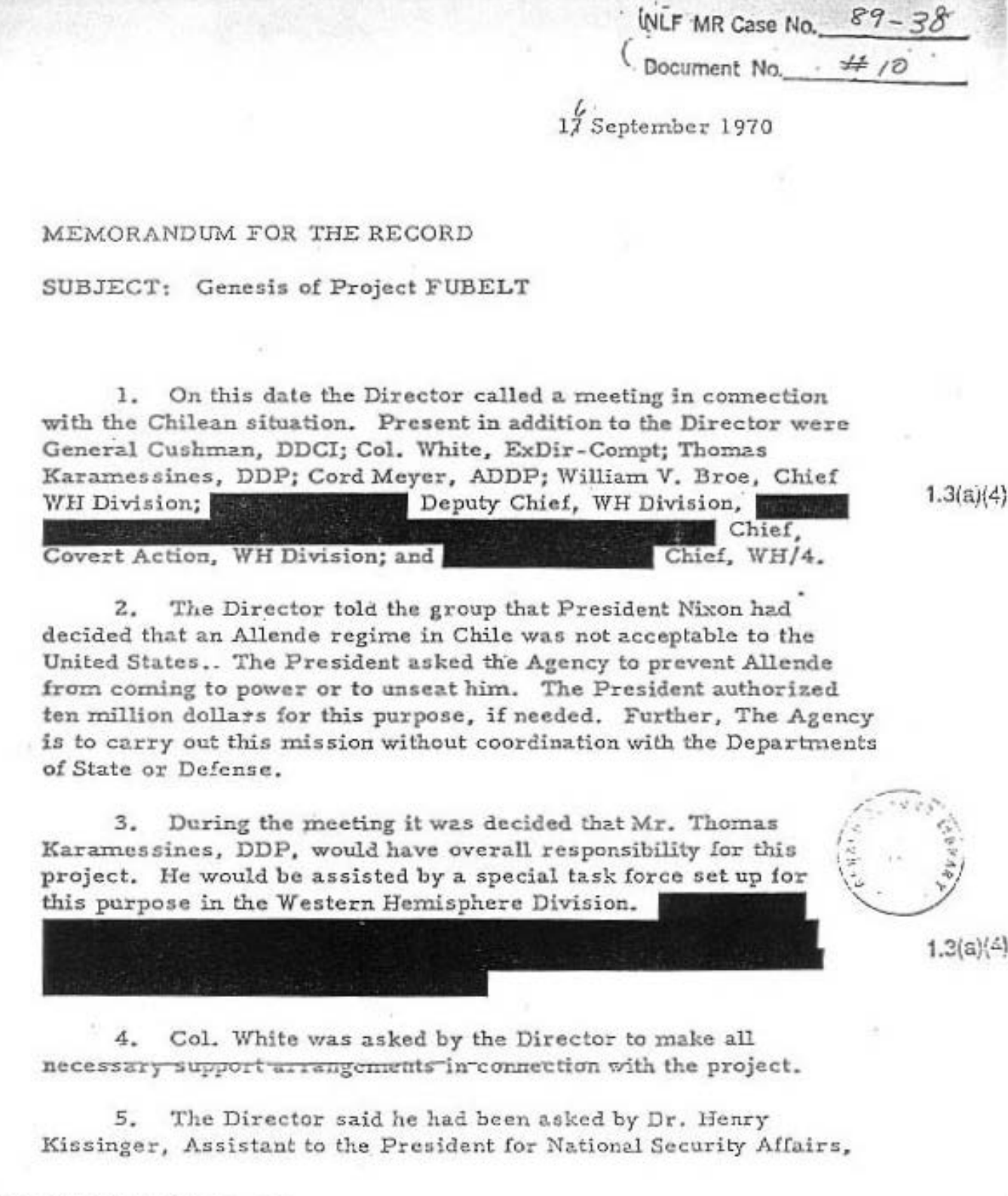

Documented evidence, including transcripts of Kissinger’s telephone conversations, show his ‘singular contribution to the denouement of democracy and rise of dictatorship in Chile.’ Eight days after Allende’s election, Kissinger had a conversation with the director of the CIA, in which he stated that: ‘We will not let Chile go down the drain.’ He rejected advice from his top deputy to refrain from covert action against the new government and ‘lobbied President Nixon to reject the State Department’s recommendation that the U.S. seek a modus vivendi with Allende.’

The day after he met with Kissinger to assess the situation, Nixon made it clear to the entire National Security Council that the policy would be to bring Allende down. ‘Our main concern,’ he stated, ‘is the prospect that he can consolidate himself and the picture projected to the world will be his success.’

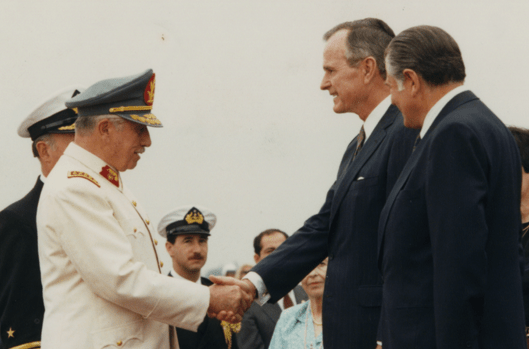

After General Augusto Pinochet had carried out his coup and launched a wave of repression that would claim tens of thousands of lives, Kissinger ‘sent secret instructions to his ambassador to convey to the general “our strongest desires to cooperate closely and establish firm basis for cordial and most constructive relationship.” Facing revelations of mass murder by the coup regime, Kissinger coolly asserted that “I think we should understand our policy – that however unpleasant they act, this government is better for us than Allende was”.’

By the most cautious reckoning, the number of people who died as a result of military violence and state repression which was orchestrated by Kissinger reaches into the hundreds of thousands. Millions more have survived under brutal regimes Kissinger helped to install or preserve, whose purpose was to enforce their poverty and exploitation.

As Kissinger adds weight to the old saying that only the good die young, he will be promoted as a distinguished elder statesman, and this is no miscalculation on the part of the establishment of which he is a part. Since he stepped back from the front lines of imperialist geopolitics, others have built upon his legacy, in Afghanistan and Iraq and many other parts of the world.

At this time of heightened global rivalry, Henry Kissinger’s vile deeds are both a road map and a source of inspiration to those who have taken his place. He has lived far too long, but the system of global violence and exploitation he furthered can’t be buried soon enough.

Throughout history for the past 100 years, very few Americans know of the damaged caused and millions killed by this criminal called Henry Kissinger.

Throughout its history, the United States has used its military and covert operations to overthrow or prop up foreign governments in the name of preserving U.S. strategic and business interests.

U.S. intervention in foreign governments began with attacks on and displacement of sovereign tribal nations in North America. In the 1890s, this type of imperialist activity, fueled by the idea of Manifest Destiny, expanded overseas when the U.S. overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom and annexed its islands. As America annexed more overseas territories for its empire, it began to intervene frequently in other countries’ governments—particularly those in its backyard.

“During the early 20th century, the United States intervened relentlessly in the Caribbean Basin,” says Stephen Kinzer, a senior fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University and author of Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq.

After World War II, the United States began using the newly established Central Intelligence Agency to overthrow governments all over the world in a more covert manner. U.S. leaders rationalized many of these interventions as necessary for preventing the spread of communism according to the Cold War domino theory. Similarly, 21st-century leaders would later defend U.S. Middle East interventions as necessary for fighting terrorism.

1893: Hawaii

In January 1893, a small group of white business and plantation owners, with the support of a U.S. envoy to Hawaii (Native spelling: Hawai’i), led a coup d’état that ousted the Hawaiian monarch Queen Liliʻuokalani from power. This came six years after the Queen’s predecessor, her brother King David Kalakaua, was forced to sign a new constitution at gunpoint that stripped him of most of his powers and shifted them to members of the white planter class.

The coup leaders immediately pushed for the U.S. to annex Hawaii, which it did in 1898. The islands remained a U.S. territory until 1959, when Hawaii became America’s 50th state.

In 1993, a century after the coup, the U.S. government formally apologized to Native Hawaiians for overthrowing their monarchy and annexing 1.8 million acres of land “without the consent of or compensation to the Native Hawaiian people…or their sovereign government.”

READ MORE: Hawaii’s Long Road to Becoming America’s 50th State

1933: Cuba

In 1898, the same year the U.S. annexed Hawaii, its victory in the Spanish-American War also gave it control of Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines as U.S. territories, as well as an excuse to begin a military occupation of Cuba. After President Theodore Roosevelt asserted America’s right to intervene militarily in Latin America in 1904-5, the U.S. began to do so more frequently in the Caribbean Basin countries, including the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, Honduras—and Cuba.

After recognizing Cuba as an independent nation in 1902, the U.S. withdrew its military from the country with the caveat that it would still intervene militarily to protect American interests in the future. Over the next three decades, the U.S. frequently invaded Cuba and other Caribbean countries in the so-called “Banana Wars,” to help quash labor strikes and revolutions that threatened U.S.-owned sugar, fruit and coffee businesses.

In 1933, it backed military leader Fulgencio Batista’s coup to overthrow the Cuban government. After Fidel Castro violently ousted Batista and established the Western hemisphere’s first communist regime, President John F. Kennedy attempted to overthrow Castro’s government in the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. This failed coup not only represented America’s ongoing imperialist attitude toward its southern neighbors; it also showcased a newer interventionist arm: the CIA.

1953: Iran

After the United States established the CIA in 1947, it began to use the agency to overthrow or prop up foreign governments in a much more covert way. Before WWII, the United States didn’t try to hide its interventions in foreign governments. But with the onset of the Cold War, the United States became much more concerned about hiding its actions from the Soviet Union, Kinzer says.

“In the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, it was a priority for President Eisenhower and [Director of Central Intelligence] Allen Dulles to assure that America always had plausible deniability,” he says. “Eisenhower was probably the last president who believed that you could do these things and nobody would ever find out.”

In 1953, the CIA orchestrated a coup of Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, in order to consolidate power with Iran’s shah (or king), Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Declassified CIA documents claim the coup—known internally as Operation Ajax—was designed to prevent possible “Soviet aggression” in Iran, but Iranian-American historian Ervand Abrahamian has argued the real motivation had more to do with securing U.S. oil interests.

1954: Guatemala

In 1954, the CIA orchestrated another coup of a democratically elected leader: Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz. The CIA coup, code-named Operation PBSuccess, replaced the president with military dictator Carlos Castillo Armas in the name of stopping the spread of communism. However, the CIA’s main motivation for ousting Árbenz was the fear that his land reforms would threaten the interests of the American-owned United Fruit Company, which owned 42 percent of the nation’s land and paid no taxes.

High-ranking officials in the Eisenhower administration had close ties to the company: Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had worked for United Fruit’s U.S. law firm, and his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles, sat on its board. The CIA continued toppling Latin American governments; in the first year of the Kennedy administration, it backed an assassination in the Dominican Republic and, under Lyndon B. Johnson, it executed a 1964 coup in Brazil.

1960-1965: Congo

In 1960, the Republic of the Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) declared its independence from Belgium and democratically elected its first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. Shortly after he assumed power, President Joseph Kasavubu pushed him out of office amid a Belgian military invasion. Worried that the ensuing unrest provided fertile ground for Soviet incursion, the CIA encouraged and assisted attempts to kill Lumumba, arguing he was a communist leader akin to Castro. The CIA helped facilitate Lumumba’s capture in 1960 and assassination in 1961.

This action precipitated the Congo Crisis (1960–1965), a period in which military leader Mobutu Sese Seko consolidated power in the country. In 1965, the CIA supported Mobutu’s coup to take over the Republic of the Congo in the name of preventing the spread of communism. Mobutu became a dictator who ruled the country until 1997.

1963: South Vietnam

The Pentagon Papers, chock full of damning revelations about America’s war in Vietnam, caused a sensation when The New York Times published them in 1971. One revelation was that the CIA had funded and encouraged the 1963 coup against, and assassination of, the president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem.

By 1963, the United States had sent thousands of U.S. soldiers to Vietnam to fight the northern communist government led by President Ho Chi Minh. The U.S. initially supported Diem because he was fighting the north. However, Diem’s persecution of Buddhists made him an unpopular ruler, leading the Kennedy administration to doubt Diem’s ability to win the war. The coup and Diem’s assassination took place in early November 1963, just a few weeks before Kennedy’s assassination.

1973: Chile

When Chile elected socialist Salvador Allende as president in 1970, U.S. President Richard Nixon originally wanted to block him from taking office, or else mount a coup soon after Allende became president. On Nixon’s orders, the CIA began supporting different Chilean groups plotting to overthrow the new socialist president. In 1973, military leader Augusto Pinochet staged a coup that ousted Allende. Pinochet assumed his dictatorship the following year, ruling as Chile’s president until 1990.

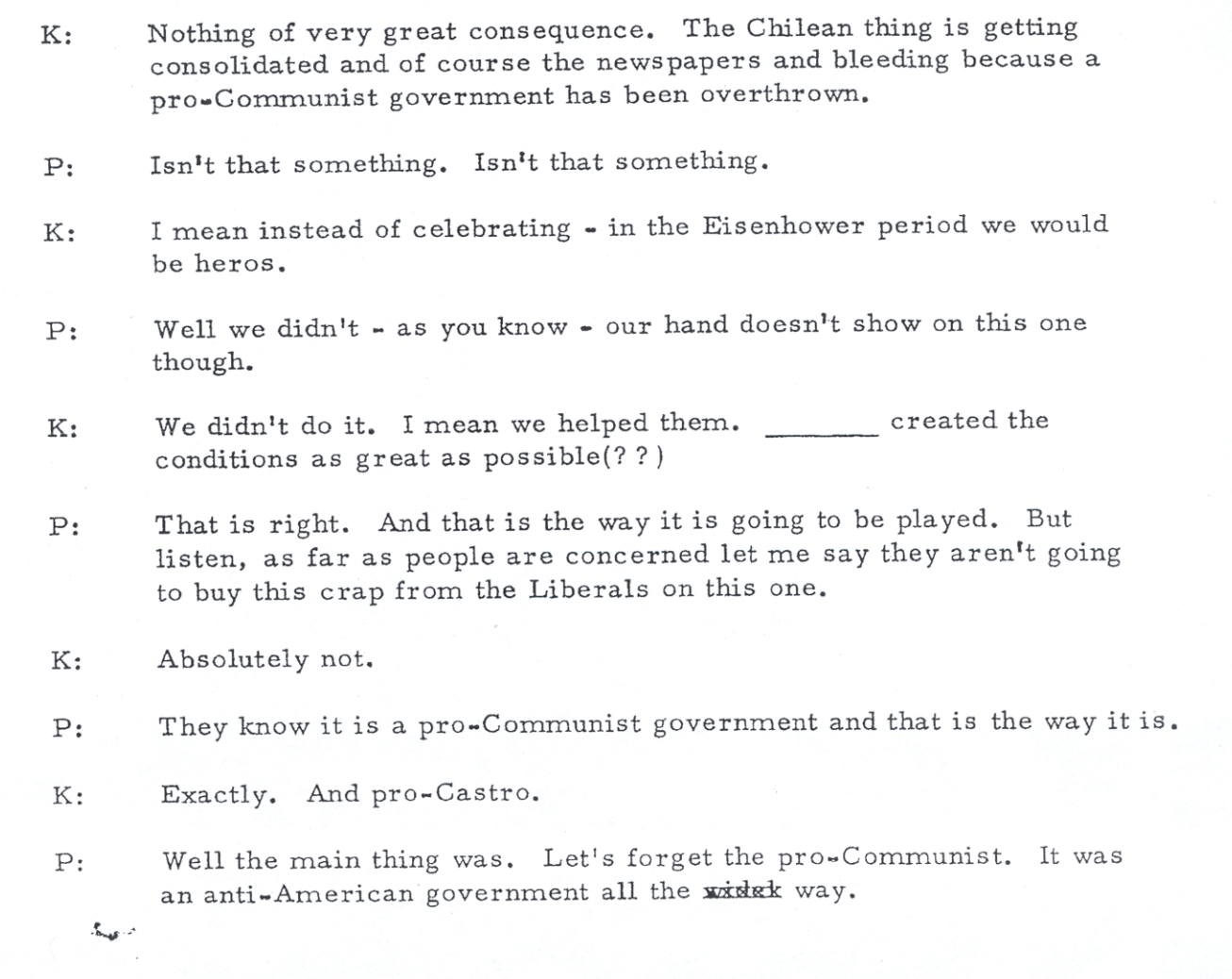

Whether the CIA was directly involved in Pinochet’s coup is still contested. However, the agency’s support of earlier coup plots contributed to political instability that Pinochet took advantage of to seize power. In a transcribed phone conversation between Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger about Pinochet’s coup, Kissinger complained that the U.S. media wasn’t celebrating the coup, complaining that “in the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes.”

“Well, we didn’t—as you know—our hand doesn’t show on this one,” Nixon responded. Kissinger clarified, “I mean we helped them…created the conditions as great as possible.”

READ MORE: How a Dictator Got Away With a Brazen Murder in D.C. in 1976

1981-90: Nicaragua

To continue watching video, please disable your ad blocking software and reload the page. For instructions, click here.

The United States has a long history of meddling in Nicaragua. Between 1912 and 1933, the U.S. military occupied the country.

Between 1981 and 1986, President Ronald Reagan’s administration secretly and illegally sold arms to Iran in order to fund Contras, a group the CIA had recruited and organized to fight the socialist Sandinista government led by Daniel Ortega. In 1986, details of the Iran-Contra Affair became public, resulting in congressional investigations. Ortega’s Sandinista government ended in 1990 with the election of opposition candidate Violeta Chamorro as president amid reports that the United States had provided funding to help her win.

2001: Afghanistan

When the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, it established an interim government led by Hamid Karzai to replace the warring Taliban government and the oppositional Northern Alliance. Karzai’s rule continued in 2002, when he became head of Afghanistan’s transitional government, and in 2004, when he became president of the U.S.-backed Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. He was succeeded in 2014 by Ashraf Ghani. Ghani was president until the Taliban retook power in 2021, when the U.S. formally ended its war in Afghanistan.

2003: Iraq

In 2003, the United States invaded Iraq and overthrew Saddam Hussein’s government. As in Afghanistan, the U.S. attempted to establish an interim, transitional and more permanent government. The United States formally ended its war in Iraq in 2011. Since then, the country’s government structure has remained in flux.

BY: BECKY LITTLE

Overthrowing Democratic Governments Is Practically an American Tradition

What’s happening in Venezuela is nothing new. The U.S. has been following the same blueprint around the world for decades. President George H.W. Bush, right, shakes hands with Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. (Wikimedia Commons)

VIJAY PRASHAD / INDEPENDENT MEDIA INSTITUTE

On September 15, 1970, U.S. President Richard Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger authorized the U.S. government to do everything possible to undermine the incoming government of the socialist president of Chile, Salvador Allende. Nixon and Kissinger, according to the notes kept by CIA Director Richard Helms, wanted to “make the economy scream” in Chile; they were “not concerned [about the] risks involved.” War was acceptable to them as long as Allende’s government was removed from power. The CIA started Project FUBELT, with $10 million as a first installment to begin the covert destabilization of the country.

U.S. business firms, such as the telecommunication giant ITT, the soft drink maker Pepsi and copper monopolies such as Anaconda and Kennecott, put pressure on the U.S. government once Allende nationalized the copper sector on July 11, 1971. Chileans celebrated this day as the Day of National Dignity (Dia de la Dignidad Nacional). The CIA began to make contact with sections of the military seen to be against Allende. Three years later, on September 11, 1973, these military men moved against Allende, who died in the regime change operation. The United States “created the conditions,” as U.S. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger put it, to which U.S. President Richard Nixon answered, “that is the way it is going to be played.” Such is the mood of international gangsterism.

Chile entered the dark night of a military dictatorship that turned over the country to U.S. monopoly firms. U.S. advisers rushed in to strengthen the nerve of General Augusto Pinochet’s cabinet.

What happened to Chile in 1973 is precisely what the United States has attempted to do in many other countries of the Global South. The most recent target for the U.S. government—and Western big business—is Venezuela. But what is happening to Venezuela is nothing unique. It faces an onslaught from the United States and its allies that is familiar to countries as far afield as Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The formula is clichéd. It is commonplace, a twelve-step plan to produce a coup climate, to create a world under the heel of the West and of Western big business.

Step One: Colonialism’s Traps. Most of the Global South remains trapped by the structures put in place by colonialism. Colonial boundaries encircled states that had the misfortune of being single-commodity producers—either sugar for Cuba or oil for Venezuela. The inability to diversify their economies meant that these countries earned the bulk of their export revenues from their singular commodities (98 percent of Venezuela’s export revenues come from oil). As long as the prices of the commodities remained high, the export revenues were secure. When the prices fell, revenue suffered. This was a legacy of colonialism. Oil prices dropped from $160.72 per barrel (June 2008) to $51.99 per barrel (January 2019). Venezuela’s export revenues collapsed in this decade.

Step Two: The Defeat of the New International Economic Order. In 1974, the countries of the Global South attempted to redo the architecture of the world economy. They called for the creation of a New International Economic Order (NIEO) that would allow them to pivot away from the colonial reliance upon one commodity and diversify their economies. Cartels of raw materials—such as oil and bauxite—were to be built so that the one-commodity country could have some control over prices of the products that they relied upon. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), founded in 1960, was a pioneer of these commodity cartels. Others were not permitted to be formed. With the defeat of OPEC over the past three decades, its members—such as Venezuela (which has the world’s largest proven oil reserves)—have not been able to control oil prices. They are at the mercy of the powerful countries of the world.

Step Three: The Death of Southern Agriculture. In November 2001, there were about 3 billion small farmers and landless peasants in the world. That month, the World Trade Organization met in Doha, Qatar, to unleash the productivity of Northern agri-business against the billions of small farmers and landless peasants of the Global South. Mechanization and large, industrial-scale farms in North America and Europe had raised productivity to about 1 to 2 million kilograms of cereals per farmer. The small farmers and landless peasants in the rest of the world struggled to grow 1,000 kilograms of cereals per farmer. They were nowhere near as productive. The Doha decision, as Samir Amin wrote, presages the annihilation of the small farmer and landless peasant. What are these men and women to do? The production per hectare is higher in the West, but the corporate takeover of agriculture (as Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Senior Fellow P. Sainath shows) leads to increased hunger as it pushes peasants off their land and leaves them to starve.

Step Four: Culture of Plunder. Emboldened by Western domination, monopoly firms act with disregard for the law. As Kambale Musavuli and I write of the Democratic Republic of Congo, its annual budget of $6 billion is routinely robbed of at least $500 million by monopoly mining firms, mostly from Canada—the country now leading the charge against Venezuela. Mispricing and tax avoidance schemes allow these large firms (Canada’s Agrium, Barrick and Suncor) to routinely steal billions of dollars from impoverished states.

Step Five: Debt as a Way of Life. Unable to raise money from commodity sales, hemmed in by a broken world agricultural system and victim of a culture of plunder, countries of the Global South have been forced to go hat in hand to commercial lenders for finance. Over the past decade, debt held by the Global South states has increased, while debt payments have ballooned by 60 percent. When commodity prices rose between 2000 and 2010, debt in the Global South decreased. As commodity prices began to fall from 2010, debts have risen. The IMF points out that of the 67 impoverished countries that they follow, 30 are in debt distress, a number that has doubled since 2013. More than 55.4 percent of Angola’s export revenue is paid to service its debt. And Angola, like Venezuela, is an oil exporter. Other oil exporters such as Ghana, Chad, Gabon and Venezuela suffer high debt to GDP ratios. Two out of five low-income countries are in deep financial distress.

Step Six: Public Finances Go to Hell. With little incoming revenue and low tax collection rates, public finances in the Global South have gone into crisis. As the UN Conference on Trade and Development points out, “public finances have continued to be suffocated.” States simply cannot put together the funds needed to maintain basic state functions. Balanced budget rules make borrowing difficult, which is compounded by the fact that banks charge high rates for money, citing the risks of lending to indebted countries.

Step Seven: Deep Cuts in Social Spending. Impossible to raise funds, trapped by the fickleness of international finance, governments are forced to make deep cuts in social spending. Education and health, food sovereignty and economic diversification—all this goes by the wayside. International agencies such as the IMF force countries to conduct “reforms,” a word that means the extermination of independence. Those countries that hold out face immense international pressure to submit under pain of extinction, as the Communist Manifesto (1848) put it.

Step Eight: Social Distress Leads to Migration. The total number of migrants in the world is now at least 68.5 million. That makes the country called Migration the 21st-largest country in the world, after Thailand and ahead of the United Kingdom. Migration has become a global reaction to the collapse of countries from one end of the planet to the other. The migration out of Venezuela is not unique to that country but is now merely the normal reaction to the global crisis. Migrants from Honduras who go northward to the United States or migrants from West Africa who go toward Europe through Libya are part of this global exodus.

Step Nine: Who Controls the Narrative? The monopoly corporate media take their orders from the elite. There is no sympathy for the structural crisis faced by governments from Afghanistan to Venezuela. Those leaders who cave to Western pressure are given a free pass by the media. As long as they conduct “reforms,” they are safe. Those countries that argue against the “reforms” are vulnerable to being attacked. Their leaders become “dictators,” their people hostages. A contested election in Bangladesh or in the Democratic Republic of Congo or in the United States is not cause for regime change. That special treatment is left for Venezuela.

Step Ten: Who’s the Real President? Regime change operations begin when the imperialists question the legitimacy of the government in power: by putting the weight of the United States behind an unelected person, calling him the new president and creating a situation where the elected leader’s authority is undermined. The coup takes place when a powerful country decides—without an election—to anoint its own proxy. That person—in Venezuela’s case Juan Guaidó—rapidly has to make it clear that he will bend to the authority of the United States. His kitchen cabinet—made up of former government officials with intimate ties to the United States (such as Harvard University’s Ricardo Hausmann and Carnegie’s Moisés Naím)—will make it clear that they want to privatize everything and sell out the Venezuelan people in the name of the Venezuelan people.

Step Eleven: Make the Economy Scream. Venezuela has faced harsh U.S. sanctions since 2014, when the U.S. Congress started down this road. The next year, U.S. President Barack Obama declared Venezuela a “threat to national security.” The economy started to scream. In recent days, the United States and the United Kingdom brazenly stole billions of dollars of Venezuelan money, placed the shackles of sanctions on its only revenue-generating sector (oil) and watched the pain flood through the country. This is what the United States did to Iran and this is what they did to Cuba. The UN says that the U.S. sanctions on Cuba have cost the small island $130 billion. Venezuela lost $6 billion for the first year of Trump’s sanctions, since they began in August 2017. More is to be lost as the days unfold. No wonder that the United Nations Special Rapporteur Idriss Jazairy says that “sanctions which can lead to starvation and medical shortages are not the answer to the crisis in Venezuela.” He said that sanctions are “not a foundation for the peaceful settlement of disputes.” Further, Jazairy said, “I am especially concerned to hear reports that these sanctions are aimed at changing the government of Venezuela.” He called for “compassion” for the people of Venezuela.

Step Twelve: Go to War. U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton held a yellow pad with the words “5,000 troops in Colombia” written on it. These are U.S. troops, already deployed in Venezuela’s neighbor. The U.S. Southern Command is ready. They are egging on Colombia and Brazil to do their bit. As the coup climate is created, a nudge will be necessary. They will go to war.

None of this is inevitable. It was not inevitable to Titina Silá, a commander of the Partido Africano para a Independència da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC) who was murdered on January 30, 1973. She fought to free her country. It is not inevitable to the people of Venezuela, who continue to fight to defend their revolution. It is not inevitable to Tricontinental: Institute for Social Change’s friends at CodePink: Women for Peace, whose Medea Benjamin walked into a meeting of the Organization of American States and said: No!

It is time to say No to regime change intervention. There is no middle ground.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.